The Altar of the Abyss: Desire, crime, and the ghost’s flesh in "Bob".

- Richard Caeiro

- Jan 7

- 2 min read

By Richard Caeiro

Alberto Martín-Aragón’s work, "Bob," operates on a frequency of psychological and metaphysical horror that mainstream cinema rarely dares to touch. Through rigorous black-and-white cinematography and an aesthetic reminiscent of surrealist nightmares, the film drags us into the deformed grief of Harper. What manifests on the screen is not just a story of loss, but an open wound exploring the dangerous boundary between memory, desire, and madness—where the image ceases to be a representation and becomes a visceral intervention in the viewer's psyche.

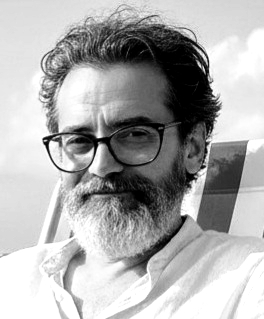

While we might initially believe we are witnessing a widow inconsolable in her morbid relationship with her husband’s ashes, the narrative soon reveals a much darker emotional geography: that of a woman who inhabits not just absence, but the very execution of her past. The film is a sensory cacophony where sound takes on a leading and disturbing role. Martín-Aragón uses guttural noises, mouth sounds, and overlapping languages like the scream of the "Id"—that part of the unconscious that knows no morality, only primitive impulse. When Harper slides the urn over her belly, transforming Bob’s remains into an object of almost sexual pleasure, the director delivers one of the most potent images in recent experimental cinema: the triumph of Thanatos over Eros, where pleasure is born from tactile contact with the end. It is grief transformed into fetish; a desperate attempt to hold onto the warmth of someone who is now merely dust. Philosophically, the clash between Harper and Bob’s sister, Evelyn, evokes the tension between secret and truth—or, as Heidegger would put it, between the concealing and unconcealing of being. Evelyn acts as the reality principle trying to invade a narcissistic and sickly dream. The revelation that the love was never returned—and the silent confession looming over the origin of that death—transforms the work into an investigation into the cannibalistic nature of affection. Love, when unrequited, decides that the beloved object cannot belong to anyone else, not even to life itself. Visually, "Bob" operates as an unusual photographic essay. The use of blown out lights and shots that seem suspended in time creates a spatial disorientation that places us inside the characters' feverish minds. The most fascinating metalinguistic detail is the fact that Alberto Martín-Aragón himself lends his face to the photo on the urn.

The director does not just conduct the work; he immolates himself within it, becoming the corpse at the center of this dark desire. It is a cinema of psychological investigation that reminds us that sometimes, the ghosts that haunt us the most are those we manufacture ourselves so we never have to say goodbye. In the end, "Bob" seeks not to heal the viewer, but to immerse them in the terrible beauty of a shared secret, proving that experimental cinema remains the most fertile laboratory for understanding the shadows that define us.

_edited.png)

Comments