The Anatomy of Emptiness: Sensation and Metamorphosis in "WarehouseMannequin"

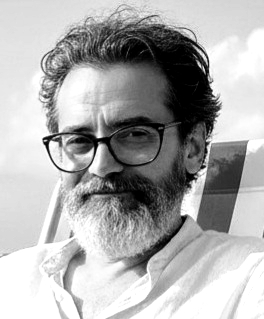

- Richard Caeiro

- Jan 26

- 2 min read

By Richard Caeiro

When we stand before an experimental film, the first step is to abandon the crutch of rational interpretation. We never know exactly what the director intended to "say," and in Karen Belfo’s "Warehouse Mannequin", this uncertainty is our greatest virtue.

The film does not hand us a pre-chewed message; it operates within the grammar of pure sensation. Upon entering this abandoned warehouse, Belfo’s camera does not seek a story but performs a visual autopsy where the image is not an answer, but an invitation to estrangement.

The work places us before helpless mannequins, yet what we see are not just plastic simulacra; it is the very memory of labor and consumption petrified into anthropomorphic forms. The use of off-screen sound—the insistent ringing of telephones, the clacking of keys, and echoes of children’s voices—functions as specters of a productivity that no longer inhabits those shells. It is the sound of capital outliving the absence of living bodies. As the camera travels over the naked, impersonal curves of these objects, we are forced to confront the commodification of life: the human body reduced to a product, to "more of the same" serialized in an inventory of disposable existences.

However, the fascination of "Warehouse Mannequin" lies in its ability to provoke a

mutation in our perception. The aesthetic rupture occurs when Belfo abandons naturalism and plunges the screen into washes of blue and purple, accompanied by sonic cacophonies that destabilize the viewer. In that instant, the film ceases to be a record and becomes an experience of metamorphosis. Confronted by the aggressiveness of these images, we cease to be passive observers. Jean-Claude Bernadet (a Belgian-Brazilian film critic and theorist) would say that the work is only completed when we allow the film to transform us; we metamorphose alongside the plastic. Belfo’s warehouse thus functions as a laboratory of subjectivities. If the human there appears as a sold object, the viewer is summoned to reclaim their humanity through the confrontation with emptiness. Karen Belfo offers us the wreckage of a system but gives us the sovereign freedom to reconstruct our own meaning from these fragments. It is a cinematic experience that is not only seen with the eyes but with the weight of one's own existence, proving that meaning is the price we pay to leave this warehouse transformed.

_edited.png)

Comments